Washington Monument

| Washington Monument | |

|

|

| Location: | Washington D.C. |

| Coordinates: | |

| Area: | 106.01 acres (0.4290 km2) |

| Visitation: | 467,550 (2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Location of Washington Monument in USA

|

|

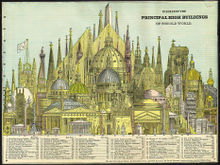

The Washington Monument is an obelisk near the west end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate the first U.S. president, General George Washington. The monument, made of marble, granite, and sandstone, is both the world's tallest stone structure and the world's tallest obelisk, standing 555 feet 5⅛ inches (169.294 m).[n 1] There are taller monumental columns, but they are neither all stone nor true obelisks.[n 2] It is also the tallest structure in Washington D.C.. It was designed by Robert Mills, an architect of the 1840s. The actual construction of the monument began in 1848 but was not completed until 1884, almost 30 years after the architect's death. This hiatus in construction happened because of co-option by the Know Nothing party, a lack of funds, and the intervention of the American Civil War. A difference in shading of the marble, visible approximately 150 feet (46 m or 27%) up, shows where construction was halted for a number of years. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1848; the capstone was set on December 6, 1884, and the completed monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885. It officially opened October 9, 1888. Upon completion, it became the world's tallest structure, a title previously held by the Cologne Cathedral. The monument held this designation until 1889, when the Eiffel Tower was completed in Paris, France. The monument stands due east of the Reflecting Pool and the Lincoln Memorial.

Contents |

History

Motivation

Among the Founding Fathers of the United States, George Washington earned the title "Father of the Country" in president of the Constitutional Convention, he helped guide the deliberations to form a government that has lasted for more than 200 years. Two years later he was unanimously elected the President of the United States. Washington defined the Presidency and helped develop the relationships among the three branches of government. He established precedents which successfully launched the new government on its course. He refused the trappings of power and veered from monarchical government and traditions and twice—despite considerable pressure to do otherwise—gave up the most powerful position in the Americas. Washington remained ever mindful of the ramifications of his decisions and actions. With this monument the citizens of the United States show their enduring gratitude and respect.

When the Revolutionary War ended, no one in the United States commanded more respect than Washington. Americans celebrated his ability to win the war despite limited supplies and inexperienced men, and they admired his decision to refuse a salary and accept only reimbursements for his expenses. Their regard increased further when it became known that he had rejected a proposal by some of his officers to make him king of the new country. It was not only what Washington did but the way he did it: Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, described him as "polite with dignity, affable without familiarity, distant without haughtiness, grave without austerity, modest, wise, and good."[6] Washington retired to his plantation at Mount Vernon after the war, but he soon had to decide whether to return to public life. As it became clear the Articles of Confederation had left the federal government too weak to levy taxes, regulate trade, or control its borders, men such as James Madison began calling for a convention that would strengthen its authority. Washington was reluctant to attend because he had business affairs to manage at Mount Vernon. If he did not go to Philadelphia, however, he worried about his reputation and about the future of the country. He finally decided that, since "to see this nation happy... is so much the wish of my soul," he would serve as one of Virginia's representatives. The other delegates during the summer of 1787 chose him to preside over their deliberations, which ultimately produced the U.S. Constitution.[6]

A key part of the Constitution was the development of the office of president of the United States. No one seemed more qualified to fill that position than Washington, and in 1789 he began the first of his two terms. He used the nation's respect for him to develop respect for this new office, but he simultaneously tried to quiet fears that the president would become as powerful as the king the new country had fought against. He tried to create the kind of solid government he thought the nation needed, supporting a national bank, collecting taxes to pay for expenses, and strengthening the Army and Navy. Though many people wanted him to stay for a third term, in 1797 he again retired to Mount Vernon.[6] Washington died suddenly two years later. His death restarted attempts to honor him. As early as 1783, the Continental Congress had resolved "That an equestrian statue of George Washington be erected at the place where the residence of Congress shall be established." The proposal called for engraving on the statue which explained it had been erected "in honor of George Washington, the illustrious Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States of America during the war which vindicated and secured their liberty, sovereignty, and independence." Currently, the only equestrian statue of President Washington is Washington Circle at the intersection of the Foggy Bottom and West End neighborhoods at the north end of the George Washington University.

Ten days after Washington's death, a Congressional committee recommended a different type of monument. John Marshall, a Representative from Virginia (who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) proposed that a tomb be erected within the Capitol. But a lack of funds, disagreement over what type of memorial would best honor the country's first president, and the Washington family's reluctance to move his body prevented progress on any project.[6]

Design

Progress towards a memorial finally began in 1832. That year, which marked the 100th anniversary of Washington's birth, a large group of concerned citizens formed the Washington National Monument Society. They began collecting donations, much in the way Blodgett had suggested. By the middle of the 1830s, they had raised over $28,000 ($594,142 in 2010 dollars[7]) and announced a competition for the design of the memorial.

On September 23, 1835, the board of managers of the society described their expectations:

It is proposed that the contemplated monument shall be like him in whose honor it is to be constructed, unparalleled in the world, and commensurate with the gratitude, liberality, and patriotism of the people by whom it is to be erected... [It] should blend stupendousness with elegance, and be of such magnitude and beauty as to be an object of pride to the American people, and of admiration to all who see it. Its material is intended to be wholly American, and to be of marble and granite brought from each state, that each state may participate in the glory of contributing material as well as in funds to its construction.

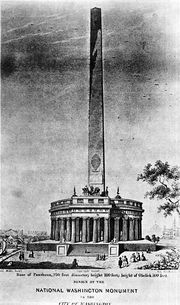

The society held a competition for designs in 1836. The winner, architect Robert Mills, was well-qualified for the commission. The citizens of Baltimore had chosen him to build a monument to Washington, and he had designed a tall Greek column surmounted by a statue of the President. Mills also knew the capital well, having just been chosen Architect of Public Buildings for Washington.

His design called for a 600 feet (180 m) tall obelisk—an upright, four-sided pillar that tapers as it rises—with a nearly flat top. He surrounded the obelisk with a circular colonnade, the top of which would feature Washington standing in a chariot. Inside the colonnade would be statues of 30 prominent Revolutionary War heroes.

One part of Mills' elaborate design that was built was the doorway surmounted by an Egyptian-style Winged sun. It was removed when construction resumed after 1884. A photo can be seen in The Egyptian Revival by Richard G. Carrot.[8]

Yet criticism of Mills' design and its estimated price tag of more than $1 million (over $21 million in 2008 dollars[9]) caused the society to hesitate. At least 100 years ago, its members decided to start building the obelisk and to leave the question of the colonnade for later. They believed that if they used the $87,000 they had already collected to start work, the appearance of the monument would spur further donations that would allow them to complete the project.

Construction

The Washington - Monument was originally intended to be located at the point at which a line running directly south from the center of the White House crossed a line running directly west from the center of the Capitol. Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of t(he) government of the United States ..." designated this point as the location of the equestrian statue of George Washington that the Continental Congress had voted for in 1783.[10][n 3] However, the ground at the intended location proved to be too unstable to support a structure as heavy as the planned obelisk. The Jefferson Pier, a small monolith 390 feet (119 m) WNW of the Monument, now stands at the intended site of the structure.

Excavation for the foundation of the Monument began in early 1848.[14] The cornerstone was laid as part of an elaborate Fourth of July ceremony hosted by the Freemasons, a worldwide fraternal organization to which Washington belonged. Speeches that day showed the country continued to revere Washington. One celebrant noted, "No more Washingtons shall come in our time ... But his virtues are stamped on the heart of mankind. He who is great in the battlefield looks upward to the generalship of Washington. He who grows wise in counsel feels that he is imitating Washington. He who can resign power against the wishes of a people, has in his eye the bright example of Washington."

Construction continued until 1854, when donations ran out. The next year, Congress voted to appropriate $200,000 to continue the work but rescinded before the money could be spent. This reversal came because of a new policy the society had adopted in 1849. It had agreed, after a request from some Alabamians, to encourage all states and territories to donate commemorative stones that could be fitted into the interior walls. Members of the society believed this practice would make citizens feel they had a part in building the monument, and it would cut costs by limiting the amount of stone that had to be bought. Blocks of Maryland marble, granite and sandstone steadily appeared at the site. American Indian tribes, professional organizations, societies, businesses and foreign nations donated stones that were 4 feet by 2 feet by 12–18 inches (1.2 m by 0.6 m by 0.3 – 0.5 m). One stone was donated by the Ryūkyū Kingdom and brought back by Commodore Matthew C. Perry,[15] but never arrived in Washington (it was replaced in 1989).[16] Many of the stones donated for the monument, however, carried inscriptions which did not commemorate George Washington. For example, one from the Templars of Honor and Temperance stated "We will not buy, sell, or use as a beverage, any spiritous or malt liquors, Wine, Cider, or any other Alcoholic Liquor." It was just one commemorative stone that started the events that stopped the Congressional appropriation and ultimately construction altogether. In the early 1850s, Pope Pius IX contributed a block of marble. In March 1854, members of the anti-Catholic, nativist American Party—better known as the "Know-Nothings"—stole the Pope's stone as a protest and supposedly threw it into the Potomac (it was replaced in 1982). Then, in order to make sure the monument fit the definition of "American" at that time, the Know-Nothings conducted an election so they could take over the entire society" . Congress immediately rescinded its $200,000 contribution.

The Know-Nothings retained control of the society until 1858, adding 13 courses of masonry to the monument—all of which was of such poor quality it was later removed. Unable to collect enough money to finish work, they increasingly lost public support. The Know-Nothings eventually gave up and returned all records to the original society, but the stoppage in construction continued into, then after, the Civil War.

Interest in the monument grew after the Civil War ended. Engineers studied the foundation several times to see whether it remained strong enough. In 1876, the Centennial of the Declaration of Independence, Congress agreed to appropriate another $200,000 to resume construction.[14] The monument, which had stood for nearly 20 years at less than one-third of its proposed height, now seemed ready for completion.

Before work could begin again, however, arguments about the most appropriate design resumed. Many people thought a simple obelisk, one without the colonnade, would be too bare. Architect Mills was reputed to have said omitting the colonnade would make the monument look like "a stalk of asparagus"; another critic said it offered "little... to be proud of."[6]

This attitude led people to submit alternative designs. Both the Washington National Monument Society and Congress held discussions about how the monument should be finished. The society considered five new designs, concluding that the one by William Wetmore Story seemed "vastly superior in artistic taste and beauty." Congress deliberated over those five as well as Mills' original; while it was deciding, it ordered work on the obelisk to continue. Finally, the members of the society agreed to abandon the colonnade and alter the obelisk so it conformed to classical Egyptian proportions.

Construction resumed in 1879 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Casey redesigned the foundation, strengthening it so it could support a structure that ultimately weighed more than 40,000 tons. He then followed the society's orders and figured out what to do with the commemorative stones that had accumulated. Though many people ridiculed them, Casey managed to install most of the stones in the interior walls—one stone was found at the bottom of the elevator shaft in 1951.[16] One difficulty that is visible to this day is that the builders were unable to find the same quarry stone used in the initial construction and, as a result, the bottom third of the monument is a slightly lighter shade than the rest of the construction.

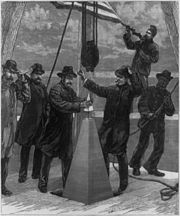

The building of the monument proceeded quickly after Congress had provided sufficient funding. In four years, it was finally completed, with the 100 ounce (2.85 kg) aluminum tip/lightning-rod being put in place on December 6, 1884.[14] It was the largest single piece of aluminum cast at the time. In 1884 aluminum was as expensive as silver, both $1 per ounce.[5] Over time, however, the price of the metal dropped; the invention of the Hall-Héroult process in 1886 caused the high price of aluminum to permanently collapse.[17] The monument opened to the public on October 9, 1888.[18]

Dedication

The Monument was formally dedicated on February 22 (Washington's birthday), 1885. Over 800 people attended to hear speeches by Ohio senator John Sherman, William Wilson Corcoran (of the Washington National Monument Society), Thomas Lincoln Casey of the Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. President Chester Arthur.[14] After the speeches General William Tecumseh Sherman led a procession, which included the dignitaries and the crowd, to the east main entrance of the Capitol building, where President Arthur received passing troops. Then, in the House Chamber, the president, his Cabinet, diplomats and others listened to Representative John Davis Long read a speech given 37 years earlier at the laying of the cornerstone. A final speech was given by Virginia governor John W. Daniel.[19]

Later history

At the time of its construction, it was the tallest building in the world; it remains the tallest stone structure in the world.[n 2] It is still the tallest building in Washington, D.C.; the Heights of Buildings Act of 1910 restricts new building heights to no more than 20 feet (6.1 m) greater than the width of the adjacent street. (There is a popular misconception that the law specifically states that no building may be taller than the Washington Monument, but in fact the law makes no mention of it).[20] This monument is vastly taller than the obelisks around the capitals of Europe and in Egypt, but ordinary antique obelisks were quarried as a monolithic block of stone, and were therefore seldom taller than around 100 feet (30 m).

The Washington Monument brought enormous crowds even before it officially opened. During the six months that followed its dedication, 10,041 people climbed the 897 steps and 50 landings to the top. After the elevator that had been used to raise building materials was altered so that it could carry passengers, the number of visitors grew rapidly. The original elevator was a steam elevator and took 20 minutes to go to the top. Wine and cheese were served to those riding, but only men were allowed on board since the elevator was considered unsafe. If women and children wanted to get to the top, they had to climb the 897 steps and 50 landings. As early as 1888, an average of 55,000 people per month went to the top, and today the Washington Monument has more than 800,000 visitors each year. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the national memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. The stairs are no longer accessible to the general public due to safety issues and vandalism of the interior commemorative plaques.

For ten hours in December 1982, the Washington Monument was "held hostage" by a nuclear arms protester, Norman Mayer, claiming to have explosives in a van he drove up to the monument's base. Eight tourists trapped in the monument at the time the standoff began were set free, and the incident ended with U.S. Park Police opening fire on Mayer, killing him. The monument was undamaged in the incident, and it was discovered later that Mayer did not have explosives.[21][22]

The monument underwent extensive renovation between 1998 and 2000. During this time it was completely covered in scaffolding.[23]

Construction details

The completed monument stands 555 ft 5⅛ in (169.294 m) tall,[n 1] with the following construction materials and details:

- Phase One (1848 to 1858): To the 152-foot (46 m) level, under the direction of Superintendent William Daugherty.

-

- Exterior: White marble from Texas, Maryland (adjacent to and east of north I-83 near the Warren Road exit in Cockeysville)

- Exterior: White marble, four courses or rows, from Sheffield, Massachusetts

- Phase Two (1878 to 1888): Work completed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas L. Casey.

-

- Exterior: White marble from a different Cockeysville quarry.[24]

- Structural: Bluestone gneiss[1]

- Commemorative stones: granite, marble, limestone, sandstone, soapstone, jade[16]

- Pyramidal point was cast by William Frishmuth from aluminum, at the time a rare metal as valuable as silver.[5] Before the installation it was put on public display and stepped over by visitors who could later say they had "stepped over the top of the Washington Monument".

The cost of the monument was $1,187,710.[14]

Inscriptions

The four faces of the pyramidal point all bear inscriptions[25] in cursive letters:[5]

| North face | West face | South face | East face |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Commission at Setting of Capstone Chester A. Arthur W. W. Corcoran, Chairman M. E. Bell Edward Clark John Newton Act of August 2, 1876 |

Corner Stone Laid on Bed of Foundation July 4, 1848 First Stone at Height of 152 feet laid August 7, 1880 Capstone set December 6, 1884 |

Chief Engineer and Architect, Thos. Lincoln Casey, Colonel, Corps of Engineers Assistants: George W. Davis, Captain, 14th Infantry Bernard R. Green, Civil Engineer Master Mechanic P. H. McLaughlin |

Laus Deo |

Halfway up the steps of the monument is an inscription in Welsh: Fy iaith, fy ngwlad, fy nghenedl Cymru — Cymry am byth (My language, my land, my nation of Wales — Wales for ever). The reason for this inscription and its author are unknown.[26]

On the 24th landing of the Monument, stones quote the Bible verses Proverbs 10:7, Proverbs 22:6, and Luke 17:6. These stones were presented by the Sunday Schools of the Methodist Episcopal Church in New York and from the Sabbath School children of the Methodist Episcopal church in Philadelphia. [27][28]

Exterior structure

|

The top of the monument.

|

Fireworks over the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool

|

|

Washington Monument at night from the Jefferson Memorial, reflecting in the Tidal Basin.

|

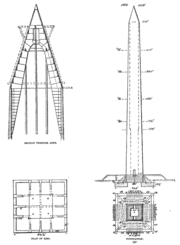

- Total height of monument:[n 1] 555 ft 5⅛ in (169.294 m)

- Height from lobby to observation level: 500 feet (152 m)

- Width at base of monument: 55 ft 1½ in (16.802 m)

- Width at top of shaft: 34 ft 5 in (10.49 m)

- Thickness of monument walls at base: 15 feet (4.6 m)

- Thickness of monument walls at observation level: 18 inches (460 mm)

- Total weight of monument: 90,854 short tons (82,421 t)

- Total number of blocks in monument: 36,491

- Sway of monument in 30-mile-per-hour (48 km/h) wind: 0.125 inches (3.2 mm)

Capstone

- Capstone weight: 3,300 pounds (1.5 t)

- Capstone cuneiform keystone measures 5.16 feet (1.57 m) from base to the top

- Each side of the capstone base: 3 feet (910 mm)

- Width of aluminum tip: 5.6 inches (140 mm) on each of its four sides

- Height of aluminum tip from its base: 8.9 inches (230 mm)

- Weight of aluminum tip on capstone: 100 oz (2.85 kg)

Foundation

- Depth: 36 ft 10 in (11.23 m)

- Weight: 36,912 short tons (33,486 metric tons)

- Area: 16,001 square feet (1,486.5 m2)

Interior

- Number of commemorative stones in stairwell: 193[16]

- Present elevator installed: 1998

- Present elevator cab installed: 2001

- Elevator travel time: 90 seconds

- Number of steps in stairwell: 897

- Fastest known ascent time via stairs: 6.7 minutes (in 2005)

In popular culture

As an iconic landmark of Washington, D.C., the Washington Monument has featured in a number of film and television depictions. The symbolic meaning of the shape is referenced in the novel The Lost Symbol by Dan Brown.[29] Its phallic resemblance is referenced in The Simpson's episode "Mr. Lisa Goes to Washington" and the Futurama episode "A Taste of Freedom",[30] (Which has the obelisk dwarfed by another called the 'Clinton Monument')and its simplistic design is denigrated in The Simpsons episode "Father Knows Worst".[31]

The monument is a target for destruction in sci-fi/disaster films, comics and video games. It is destroyed in sci-fi/disaster films such Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, Mars Attacks! and 2012. It was destroyed in the Marvel Comics series X-Factor during a superhuman fight.[32] In the DC Comics series called Guy Gardner: Warrior, it was toppled in a battle.[33] In the same continuity, it was rebuilt. It was again demolished in the limited series Amazons Attack!.[34] In video games such as Modern Warfare 2 it serves as a touchstone for a supposed evacuation of the city of Washington. In the game Fallout 3, the damaged monument is frequently visible to the player while outdoors, and it can be visited and ascended. Note that the depictions of the monument in Modern Warfare 2 and Fallout 3 are fanciful, as the monument is almost entirely supported by the masonry, not an internal metal superstructure.[35]

One of the missions of the video game Splinter Cell: Conviction takes place around a county fair in front of the monument. The entrance of the monument serves as a meeting place for protagonist Sam Fisher with his old friend Victor Coste.

In an episode of Home Improvement, Tim Taylor and Al Borland are discussing lighting on Tool Time. Tim holds up different pictures. First, he says, "This is the kind of lighting you want if you have a pool" and holds up a picture of a pool that is lit. Second, he says, "This is the kind of lighting you want if you have a porch" and holds up a picture of a lit porch. Finally, he says, "And this is the kind of lighting you want if you have a big monument" and holds up a picture of the Washington Monument with lights surrounding it as the music Hail to the Chief plays.

See also

- List of towers

- Washington Monument Syndrome

- World's tallest free standing structure on land

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Several heights have been specified, all of which exclude the foundation whose top is about 20 feet (6 m) above the surrounding terrain. The foundation is surrounded by a roughly circular mound of earth which gradually rises from the surrounding terrain to the top of the foundation, effectively placing the foundation below ground level.[1]

- 555 feet 5⅛ inches (169.294 m) according to the National Park Service[2] given above.

- 554 feet 11½ inches (169.151 m) according to historic architectural drawings redrawn in 1994, door sill to tip.[1]

- 555 feet 5½ inches (169.304 m) according to the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, measured in 1934 using a metal chain.[3]

- 555 feet 5.9 inches (169.314 m) according to the U. S. National Geodetic Survey, measured in 1999 using GPS receivers.[3][4]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Washington Monument is the third tallest monumental column in the world after the San Jacinto Monument in Texas and the Juche Tower in North Korea.

- The San Jacinto Monument is taller by 11.9 feet (3.6 m), but it is made of reinforced concrete, not stone, even though it has a facade of limestone.

- The Juche Tower is taller by less than a meter, but its top 20 meters are metal, not stone.

- ↑ L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life, while residing in the United States. He wrote this name on his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ....." and on other legal documents.[10] However, during the early 1900's, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant".[11]

The National Park Service identifies L'Enfant as "Major Peter Charles L'Enfant" and as "Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant" on pages of its website that describe the Washington Monument.[12][13] The United States Code states in 40 U.S.C. § 3309: "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant."

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Washington Monument, High ground West of Fifteenth Street

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions about the Washington Monument by the National Park Service

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 NOAA team uses GPS to size up monumental task

- ↑ Washington Monument GPS Project

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 The Point of a Monument: A History of the aluminium Cap of the Washington Monument

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "The Washington Monument: Tribute in Stone". National Park Service, ParkNet. http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/62wash/62wash.htm.

- ↑ Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ↑ Richard G. Carrot, The Egyptian Revival, University of California press, 1978 plate 33

- ↑ Dollar Conversions From 1800 to 2016 Oregon State University.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Peter Charles L'Enfant's "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ...." in official website of the U.S. Library of Congress Accessed October 22, 2009. Freedom Plaza in downtown Washington, D.C., contains an inlay of the central portion of L'Enfant's plan and of its legends.

- ↑ Bowling, Kenneth R (2002). Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ "Washington Monument" section in "Washington, D.C.: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary" page in official website of U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Washington Monument" page in "American Presidents" section of official website of U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 413. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ Kerr, George H. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. (revised ed.) Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2003. p337n.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 The Washington Monument, A Technical History and Catalog of the Commemorative Stones page 3.

- ↑ A History of the Washington Monument: 1844–1968 by George J. Olszewski. April 1971. National Park Service. . Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ↑ "Washington Monument". Teaching with Historic Places. National Park Service. . Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 414. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ The Building Height Act of 1910, codified at D.C. Code § 6-601.05

- ↑ Washington Monument (Olin Partnership)

- ↑ Monumental Security (from the American Society of Landscape Architects website, April 10, 2006)

- ↑ Washingtonpost.com: Cleaning up a Classic

- ↑ "Building Stones of Our Nation's Capital: Washington's Building Stones". United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Washington Monument Capstone

- ↑ "Presidential connection". Star Spangled Dragon. BBC.

- ↑ http://www.just4kidsmagazine.com/beacon4god/lausdeo.html

- ↑ http://www.truthorfiction.com/rumors/w/washmonument.htm

- ↑ Hodapp, Christopher L. Deciphering The Lost Symbol 2010, Ulysses Press, ISBN: 1569757739

- ↑ Futurama: A Taste of Freedom

- ↑ Captain Obvious

- ↑ "X-Factor" Vol 1. #74-75

- ↑ "Guy Gardner: Warrior"

- ↑ "Amazons Attack!" #1-5 (2007)

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

- Harper's Weekly cartoon, February 21, 1885, the day preceding formal dedication

- Official NPS website: Washington Monument

- Today in History—December 6th

- Washington National Monument at Structurae

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Cologne Cathedral |

World's tallest structure 1884—1889 169.15 m |

Succeeded by Eiffel Tower |

|

||||||||||||||||